Peace Corps: PST Beginnings

As I write the following, it is 9:00 pm on Thursday October 2nd, and I have just finished my fourth day of training.

And as a quick aside, the government shutdown is not effecting or ending my Peace Corps training and service.

It may seem like its only been a few days since my last post, and you would be right. But the time dilation that happens during Peace Corps Pre-Service Training (PST) is unfathomable. I've only been in training for four days, but I could SWEAR its been two weeks.

The last four days have been jam-packed, long, tiring, but ultimately indescribably rewarding and fun (to me). And that reality, I suppose, is making everyday seem like three instead of one, and slowing down time.

My days begin early, so no later than 6:00 I'm up, due to a combination of necessity, sunlight, and screaming roosters. I begin with hygiene and chores, such as sweeping my floor and gathering water for the day ahead. I then rip through Sesotho flashcards for around 30 minutes, before meeting my 'Me (mother) in the kitchen to help prepare breakfast.

One thing is certain about Lesotho: the food is absolutely GAS (really good). Although, I believe this is the minority opinion in my training cohort. I guess most people don't like unseasoned meat, abundant starchy carbs such as papa (thick cornmeal) or bohobe (a pot-sized loaf of bread), thick slabs of peanut butter, moroho (cooked down greens), morning porridge, linaoa (beans, di-now-a), and the occasional scrambled mahe (mah-he, eggs) to boot.

The Lesotho diet is functional, and, as someone who spent the last two years of college eating the same breakfast/lunch/dinner repeatedly to fuel my running, I am (literally) eating it up. At lunch, all the trainees eat together, and I end up becoming a human garbage disposal, finishing off food the other volunteers don't want; Which (if you know me) you'll recognise as normal behavior for me. No food waste.

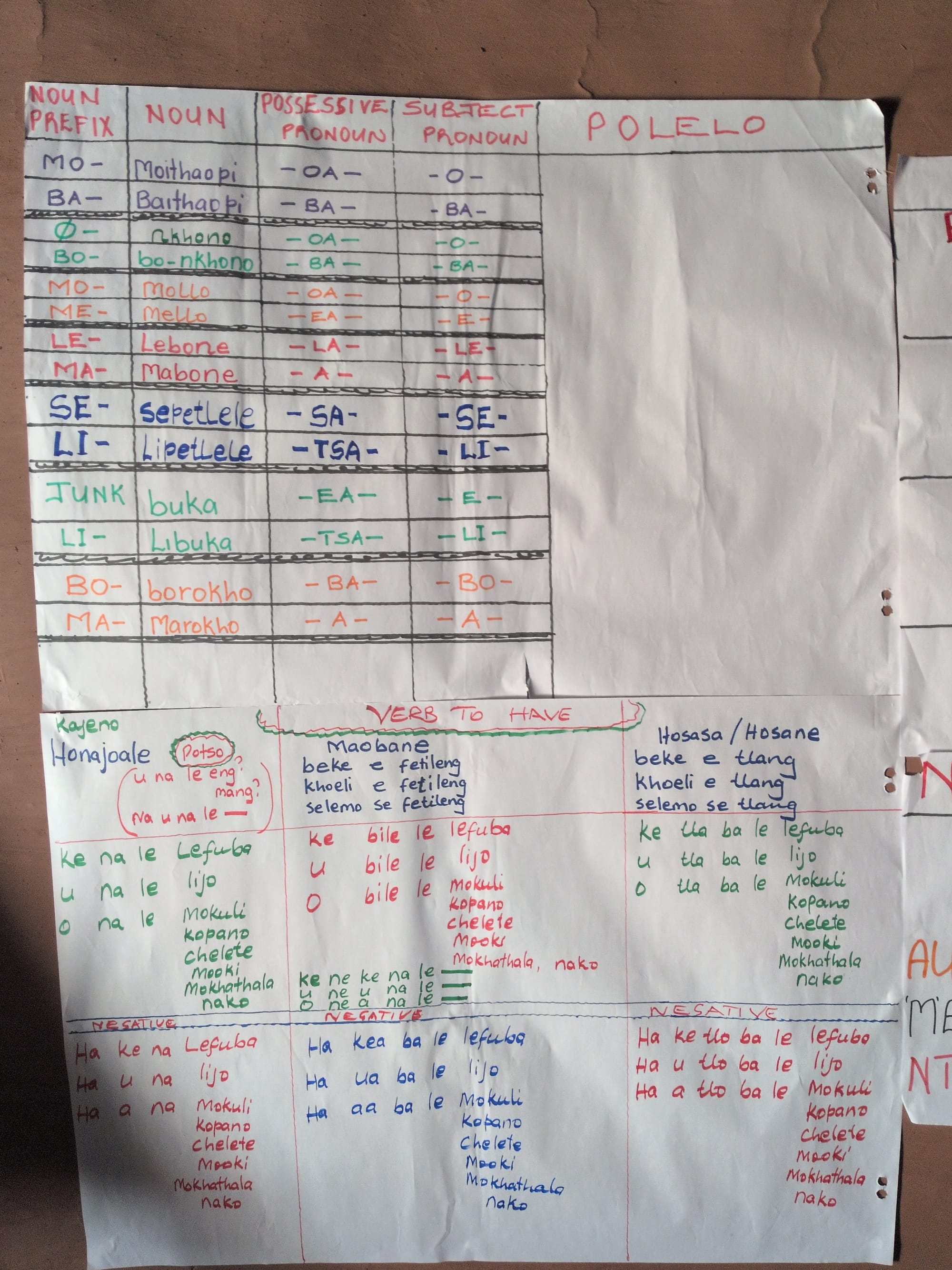

In between all the good eats, we do also have this little thing called PST: About 9-10 hours of training a day. Mostly, it's lecturing or practicing language, but there are also informal sessions, like learning to sing the Lesotho national anthem in Sesotho (the staff insisted we also learn the two part harmony at the same time, which was a hilarious and nearly impossible task). Besides language, there is technical/cultural/job-related training, which we haven't done much of yet as we are still hitting the language basics hard. But, for instance, recently the health volunteers (me and seven others) visited a real health clinic similar to the ones we will be placed in.

Much of the day is textbook "baptism by fire". Today we had to walk around the village and introduce ourselves to strangers in Sesotho; we had to say both our names (American and Basotho), where we are from, where we live now, and who we live with (in the village); And all that with zero notes. Yeah... and this was day FOUR of training. Brutal. At the end of this post, you will find an audio clip of me introducing myself in Sesotho, with a Sesotho and English transcription.

It's very awkward trying to speak to locals, because you feel like an infant putting their first phrases together (but, happily, receive similarly high levels of praise that a baby would get for their first words). The tension, however, is displaced by the sheer gratitude and happiness emanating from the Basotho whenever you attempt Sesotho. Plus, I can feel my Sesotho skills rapidly expanding each day, so the awkwardness is merely an acute ache, not a chronic endowment.

When you come to live in Lesotho, one of the first things that happens is you are given a new name, a Basotho name. My 'Me gave me the Basotho name Bohlokoa. This name means "Important", and my 'Me said she gave it to me because "You are important to my family." Some other names received include Lerato, which means love, and is Michael-esk in popularity here; Tumelo, which means Faith; And, a personal favorite, Tlhonholofatso, which means Bliss.

Blohlokoa (Boo-hlow-kwa, the middle phonic doesn't exist in English, but I pronounce it below)

Lerato (Lay-rah-toe)

Tumelo (Two-may-low)

Tlhonholofatso (you're on your own)

Lets talk my home, which is a traditional Ronduval style house: a stone/cement walled, circular, one-roomed home with a thatched roof. Inside I have everything needed to live here: clothes, pots, a water filter, buckets for carrying water, a propane stove, and a bed (which ultimately is optional, and I will likely end up on the floor again once the weather gets warmer).

I also bathe in a basin with a bar of soap and a hand towel; Bathing in this manner only takes ~2 gallons of water, making it extremely water and energy efficient. The other volunteers and Basotho boil water for bathing (mixing with cold water to get warm water), but, obviously, I've opted to forgo this step; Too much propane, takes too long, and I'm a cold-shower guy to begin with. When listing my living style quirks, one volunteer hilariously asked me: "Do you just enjoy torturing yourself?" What can I say, except, it's who I am.

The Basotho solutions to problems are practical, and I love it. Every home features a midnight piss bucket with an air-tight lid, and I cannot overstate how amazing this is; why walk out to the pit latrine, when you can just roll off the bed and be done with it in 30 seconds? Another elite example: we don't have fire extinguishers, we just have a bucket full of dirt. If my stove ever goes up in flames, you best believe I'm reaching under my table and dumping some of Lesotho's finest soil all over it.

Outside of training (and between all the other necessary tasks) we have some limited free time. I don't have the energy reserves to run hard yet, but we do often get a short'n'slow hike in before sunset and dinner. The best part of these hikes? The nature. Absolutely gorgeous, as you will see from the pictures below. We also always draw a herd of kids, and they love playing/walking with us and getting their photo taken. They literally come out of the woodwork and multiply throughout the walk; Yesterday, we started a hike with just five volunteers and ended with an additional ~15 kids by the end (pictures below).

With so much attention on us Baithaopi (volunteers, buy-tao-pee), some solitude and peace is needed. I find this in the early morning sunrises, where the clouds flow with bountiful hues of yellow, orange, and purple over the distant misty mountains. And, also in the late night awakenings, where the glow from the Khoeli (moon, Hhway-dee) casts a shadow on everything, and the stars glisten like smoldering embers above.

So, is PST intense? Yes. Are some volunteers facing hardships with integration, homesickness, and language? Yes. But I remain excited and beyond happy, and often end up helping other trainees navigate such challenges. Is this worth it? Indescribably so.

And it is only day FOUR. Mind blowing.

Pics of my home, the roof from the inside, my outside view from the door, and the farm animals/crops behind my home

Group walk with local Basotho bana (children)